Bearded

- May 12, 2023

- 5 min read

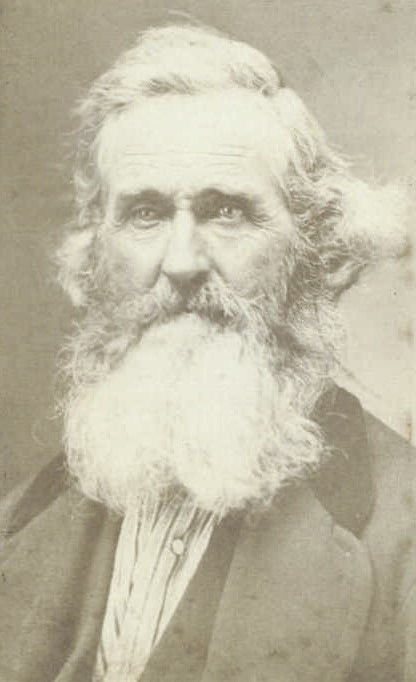

A couple of weeks ago during the 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks Challenge, I posted about a man of Solitude, Richard Higeson Thomas, and mentioned his father, my great-great-grandfather, George Calder Thomas. With this week's writing prompt of "Bearded," I thought George's exuberant whiskers deserved another look. Serendipitously, I was able to visit the place in Kansas where George built his final log-and-sod cabin, and his grave site, so he has been on my mind. And I learned that George's barbering (or lack thereof) is incidental -- his family was all about Land.

George Calder Thomas was born on April 9, 1813, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to immigrant parents. Shropshire-born Richard Thomas and Dublin-born Elizabeth Calder, had taken ship from Ireland in 1801 with their two surviving toddlers, John and Jane, having lost Richard Jr. at seven months, and settled in Philadelphia. George was the fifth of six children born to them there.

Not long after Rebecca's birth in 1817, the family emigrated yet again, to the banks of the Grand River in Upper Canada, which would soon become Canada West and is now Ontario. It's tempting to try to describe how land ownership was handled in this area, but, as my friend, Ziva, would say, "It was Clown Shoes." Courts are still trying to figure out what happened to whom; as I'm sure will surprise no one, it appears the native inhabitants of the area got the shaft.

In any event, Richard and his two eldest sons, John and William, petitioned to be granted land, saying they were Loyalists and, gosh darn it, they always had been. Personally, I find it somewhat suspicious that the Thomas family came to Pennsylvania, which had been an American state for twenty-six years at that point, spent a decade and half there, and then suddenly realized that their devotion had been to Britain all along. To be clear, I don't condemn them for their opportunism. I expect Richard and Elizabeth were tired of a system where all the available land had already been divvied up, in which, barring financial windfall beyond their wildest dreams, they would forever be at the mercy of a landlord when it came to everything from reaping a harvest to adding a room onto (someone else's) house. Their desire to have property of their own made the considerable risk of a speculative trip across the ocean seem worthwhile. I'm not sure why they weren't able to fulfill their dream in Pennsylvania. Maybe they were too busy having kids. But when they heard land was available in Canada and that the requirements for ownership were (like the Pirate's Code), more guidelines than rules, they promptly hiked themselves on up there.

William and John received their grants of land in 1824, but Richard died before his transaction was completed. I've written elsewhere about how Elizabeth explained in no uncertain terms to the Governor of Canada that she expected him to complete the grant without further delay, which he did in 1826.

In 1838, George married Matilda Strowbridge, the granddaughter of a New Jersey man who broke his father's heart and had his name was stricken from the family Bible when he declared for England during the Revolutionary War. Crispus Strowbridge had also received grants of land from the Crown. George and Matilda had six children and had built a home on land they purchased near "Brant's Ford" on the Grand River, but it seems George chafed at having missed out on the opportunity to carve out property for himself. In 1853, when their youngest child was not yet two years old, George and Elizabeth headed south, to Fort Atkinson Iowa. From there, they ranged west to Colorado, where eldest son Harvey enlisted with Union forces during the Civil War, and then even further west into Montana, where next-oldest son Richard staked his own land claim. Returning to central Iowa after the Civil War, Harvey purchased a farm, while George Jr. settled down in town, operating a variety of retail concerns which funded an eclectic collection of residential lots throughout the area. Matilda died in 1873, and the next year, George Sr. of the bushy beard and his youngest son, John, took off for the western frontier. They both staked out land claims under the Homestead Act in Rawlins County in far northwest Kansas, and, together, built a log-and-sod cabin to which John welcomed his new bride, Margaret. Keep in mind that George sixty-four years old when he made this move and, with his inexperienced 21-year-old son, hewed the dirt and the meagre supply of trees to create this home. He must have needed wide-open spaces and felt honor-bound to give his son the same opportunities he had.

From left to right -- the original sod and log house on George Calder Thomas Sr.'s land claim; the house his son, John Calder Thomas and John's wife, Margaret, built over the top of it; and the remains of the foundation today.

George Sr. died at the age of 76 in 1889, and John petitioned the court to inherit his father's claim, which had not yet been finalized. From newspaper accounts, John believed he was successful, as he offered "the farm" for sale shortly before his death in 1919, citing ill-health. But in 1941, John's namesake son sued the rest of his family -- his brothers and sisters and their children but also including "the unknown heirs, executors, administrators, devisees, trustees and assigns of G.C. Thomas, deceased" over ownership of the homestead land.

I don't know the outcome of that suit. I hope the snarly tone of the notice is merely due to legal requirements and not how the family actually felt toward one another at that point. But it does seem to be a story about a 150-year compulsion to acquire property... no matter what -- and, perhaps a cautionary tale.

I remember a high school assignment (Civics? Social Studies? It's all a blur) in which the teacher asked us how we would define "The American Dream." I blithely dashed off that it was the chance to own a home, to own property, and was a bit chastened when others remembered to talk of things that are more important, like freedom of religion and freedom of speech. But the first thing I did after getting a real job was to buy a house, and, despite my current total contentment in a 300 square foot motorhome, if pressed, my response to "the perfect home" would be something with far more rooms than I could ever use on a property far too big to take care of on my own. It's not rational, but perhaps it can be explained away as a generational imperative, something I inherited from Richard, Elizabeth and George.

I'm okay with not getting the beard, though.

Comments